High Stakes, High Stress— Is Poor Well-being an Inevitable Occupational Hazard of Legal Practice?

“When I started law school, I loved it…what I didn’t realize was the same work was also steering me onto a path of debilitating burnout.” – (McCrary, 2022)1

.

Stress and the Legal Profession: A Tale as Old as Time

Practicing law is widely regarded as one of the most stressful careers in the world. A 2022 analysis by the Washington Post of data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics revealed that being a lawyer is the most stressful occupation in the United States. In the same year (2022), the Canadian Bar Association partnered with the Federation of Law Societies of Canada and the Université de Sherbrooke, to conduct the first comprehensive national study on wellness in the Canadian legal profession, The National Study on the Psychological Health Determinants of Legal Professionals in Canada. The report found that legal professionals in all areas of practice and in all jurisdictions suffer from significantly high levels of psychological distress, depression, anxiety, burnout, and suicidal ideation, with those in the early years of practice experiencing some of the highest rates of distress.

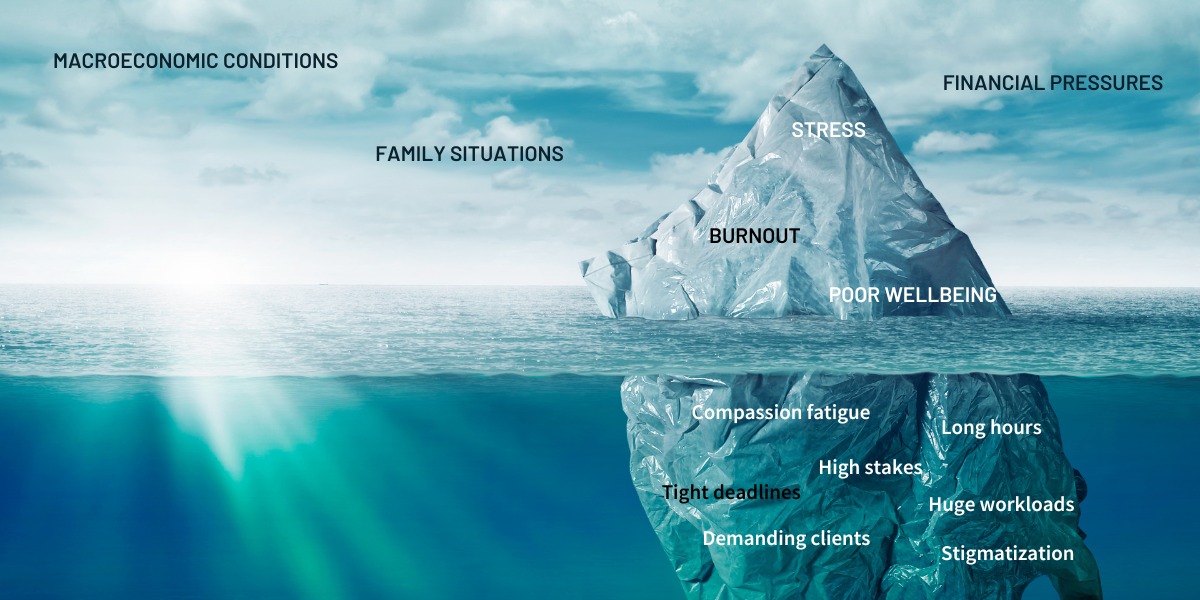

Many factors are known causes of high stress in the legal profession, including:

- Long hours, huge workloads and tight deadlines are a predominant feature of the profession, especially in early career stages, and they often result in a work-life imbalance.

- High-pressure situations, such as court hearings, negotiations, the adversarial nature of litigation, and pressure to perform, are par for the course for lawyers.

- Demanding clients can be difficult to deal with, especially when they project the negative emotions from their personal situation onto their lawyers.

- High stakes: Legal matters can have profound consequences for individuals, families, businesses, the economy and humanity (setting precedents). This places a significant burden on lawyers, who must also be diligent to avoid malpractice issues that could lead to losing their practice license.

- Compassion fatigue: Lawyers are often exposed to traumatic and emotionally challenging situations in their line of work. This constant exposure to trauma and suffering can lead to compassion fatigue, a form of burnout that results from prolonged exposure to the suffering of others. In some cases, it can also lead to vicarious trauma, where an individual may have their whole worldview shaken as a result of constantly witnessing or hearing about traumatic events experienced by others.

- The organizational culture in some law firms can be intense, with cutthroat competition and a ‘survival of the fittest ‘mentality. This environment, often perpetuated by senior partners who view it as a ‘rite of passage,’ can contribute to the high-stress levels experienced by lawyers. ‘Being a lawyer is supposed to be hard’ is a common sentiment.

- Stigmatization: If the prevailing opinion is that being a lawyer is inherently stressful, it’s possible to feel ashamed when you struggle. You might feel like the issue is your own weakness rather than the challenging nature of the work, and you should have been better prepared for the demands of the job.

Is Stress Inevitable for Lawyers?

The factors above are well-known and have become widely accepted as features, not bugs, of the legal profession. Despite the challenges and stresses associated with this career path, many people still choose to practice law. For some, it’s a calling and a way to make a difference in the world. Lawyers have the opportunity to help clients navigate complex legal issues and make a real impact on their lives.

Additionally, the intellectual challenge of law and the opportunity to work on groundbreaking cases can be rewarding for those who enjoy critical thinking and problem-solving. The personal growth and satisfaction that come with playing such a significant role in society, and the potential to make a lasting impact, can be immensely fulfilling.

The financial rewards of a successful law career can also be a motivating factor for many people. While the legal profession is not for everyone, for those who are passionate about the law, the rewards can outweigh the challenges.

If abandoning the profession is not the solution, must all lawyers inevitably endure stress?

Stress vs. Stressors

Stress and stressors are related but distinct concepts. Stressors refer to the external events, situations, or conditions that trigger a stress response in an individual. Stress refers to the physiological and psychological response that an individual experiences in response to a stressor. The stress response itself is a natural and necessary part of our body’s adaptive response to challenging situations. However, chronic or excessive stress can significantly negatively impact our health and well-being.

While potential stressors may be inevitable in the practice of law, how an individual manages or copes with them can be the difference between burnout and a thriving legal career.

It is reassuring to know that learning effective strategies to manage stressors and reduce the impact of stress on our lives is not only possible but also within reach.

Mitigating Stress by Managing Stressors

Stressor: Long hours, huge workloads and tight deadlines

Mitigation:

-

- Prioritize: Prioritize your tasks and focus on the most critical ones first. Learn to delegate tasks when possible and say no to new projects when you feel overwhelmed.

- Be organized. It may seem small, but organization goes a long way in staying on top of tasks and deadlines. It helps you feel more competent and in control of the situation and less likely to panic and induce a stress response. Keep detailed records of relevant events and documents.

-

- Leverage technology: Think of technology as your assistant, helping you be more effective and efficient at your job. From comprehensive practice management solutions to simple phone apps, technology can increase efficiency by streamlining your tasks and handling administrative functions, allowing you to focus on the parts of the law you enjoy.

- Take breaks: Taking breaks throughout the day to rest and recharge may seem counterproductive when you’re racing against time. However, it can help you be more productive and efficient, resulting in quicker task completion. Get up, move around, walk outside, or practice deep breathing exercises. Periodic vacations—where you switch off—do wonders for the mind, body, and soul. With today’s constant go-mentality, it may seem impossible to truly switch off, but it’s worth trying.

Stressors: High-pressure and high stakes situations

Mitigation:

-

- Continuous improvement and development: Information is king. Staying informed and up to date on developments in the global legal industry helps you feel competent and less stressed when dealing with high stakes constantly. Keep up with your CPD requirements and view them as beneficial to you and not just a required box to tick. Attend webinars and subscribe to helpful publications like the Dye and Durham Docket, The Brief, and other relevant publications.

-

- Pay attention to soft skills: To be a successful lawyer, you must have in-depth knowledge of the law. You should also invest time in developing skills such as client relationship management, stakeholder management, negotiation, litigation, public speaking, persuasion, etiquette, and grooming. Mastering these skills can help you feel more confident and less stressed in high-pressure situations.

Stressors: Demanding clients and Compassion fatigue

Mitigation:

-

- Set boundaries: It’s imperative to set boundaries between work and personal life. Set realistic expectations for yourself and communicate them to your colleagues and clients.

- Practice self-care: Engage in activities that promote physical and mental health, such as exercising, meditating, or spending time with loved ones. Eat properly, rest adequately, and carve out time to engage in activities you enjoy. Self-compassion is the foundation for kindness towards others.

-

- Focus on your ‘why’: Remember why you chose to practice law, whether it’s to help people, for the love of the law, or as a means to achieve your financial goals.

Stressor: Organizational culture

Mitigation:

-

- Autonomy, Consistency of Values and Support from Colleagues: The National Study on the Psychological Health Determinants of Legal Professionals in Canada revealed that autonomy (for example, freedom to decide on working methods), consistency of values (values and goals are aligned with those of the workplace) and support from colleagues (colleagues listen and offer help and recognition) are the workplace factors that have the most decisive impact on health as they are the associated with significantly lower levels of stress, psychological distress and burnout.2

“While certain constraints (including emotional demands and quantitative overload) have significant impacts on a person’s health, it turns out that some resources also carry considerable weight. In this regard, autonomy and consistency of one’s values with those of their work environment seem to have a very significant effect on reducing burnout symptoms, even surpassing the effect of certain risk factors such as hours worked and qualitative overload.” 2

Some lawyers thrive in a cut-throat environment, while others operate better in a culture of collaboration. Determine what works for you and find an organization with a culture fit—finding a place may take a while, but the long-term benefits of working in an organization where you thrive more than make up for it.

Right. What if I’m Already Burnt-out?

“One afternoon, in the summer of 2020, I was sitting in my office when a feeling of intense fear gripped me. I slipped into a loop of troubling thoughts about my life, my loved ones, and my job. The more I tried to escape it, the deeper I dove. I was scared. Very, very scared. My heartbeat quickened and aftershocks of the feeling shadowed me for days. Each time I entered my office, a familiar dread followed. My concentration dwindled. I turned to alcohol for refuge.” – (McCrary, 2022)1

Warning Signs of Burnout

- Increased irritability: more irritable or short-tempered than usual. Snapping at colleagues or clients or becoming easily frustrated by minor setbacks.

- Difficulty sleeping: trouble falling asleep, staying asleep, or waking up feeling rested.

- Decreased appetite: losing interest in food and experiencing a decrease in appetite.

- Lack of focus: difficulty concentrating on work, getting easily distracted or inability to focus on tasks for long periods.

- Feeling overwhelmed: constantly feeling like you have too much on your plate and having difficulty prioritizing tasks.

- Physical symptoms: constant headaches, back pain, and muscle tension, among others.

- Withdrawal from social interactions: isolating oneself from friends, family, or colleagues at work.

- Difficulty maintaining productivity: struggling to complete tasks on time or meet deadlines, leading to further stress and anxiety.

- Substance abuse: turning to drugs, excessive alcohol or other substances as a way to cope.

.

Get Help

If you or someone you know is experiencing these symptoms, seek support from a mental health professional or other resources available to lawyers. Stress management techniques such as exercise, mindfulness, and meditation can also help reduce stress levels. By recognizing the signs of stress and taking steps to manage it, lawyers can maintain their well-being and build a thriving, long-term career.

Remember, your health and well-being are essential, and taking steps to manage stress is an investment in your future success.

Helpful Resources

- Canadian Bar Association (CBA)

- Canadian Mental Health Association (CMHA)

- Law Societies

- Government of Canada

Visit the Dye & Durham website for more insights or to learn more about our complete suite of legal practice management solutions.

References

- McCrary, Dustin S. “What I Wish I Had Known Before Becoming a Lawyer.” Ascend. Harvard Business Review, January 6, 2022. https://hbr.org/2022/01/what-i-wish-i-had-known-before-becoming-a-lawyer.

- “The National Study on the Psychological Health Determinants of Legal Professionals in Canada.” (2022): 71-75. Accessed May 8, 2024. https://flsc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/EN_Preliminary-report_Cadieux-et-al_Universite-de-Sherbrooke_FINAL.pdf.